The US employment outcomes of the past six months point to balance between demand and supply. For the outlook, downside risks are growing.

The abrupt upturn in nonfarm payrolls employment witnessed in September and Q3’s (very) strong GDP print led the market to question whether the US economy was re-accelerating, warranting additional tightening by the FOMC. Just a month on however, a benign view for inflation has emerged. Indeed, there is now evidence of downside risks forming for both employment and consumption.

October’s 150k payroll gain was half September’s increase and also below August’s 165k. More to the point, it leaves the 3-month average at 204k, a long way short of the 342k average of the same period a year ago, and 667k a year before that (2021). 204k is still twice the 100k pace FOMC members have tabled as consistent with balance between labour demand and supply. But current population growth provides enough supply for 130k new jobs a month. And, if the trend rise in participation is also accounted for, supply has been sufficient over the past year for around 250k new jobs per month. Note as well that, during the past 12 months, total hours worked have declined 0.9%. As such, the creation of 105k new jobs has been required each month to offset hours lost by existing workers.

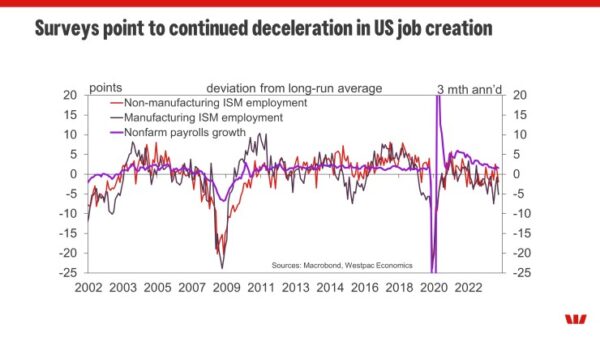

The household survey in contrast points to slack already building, the number of employed having risen just 32k per month May to October, including an average decline of 13k the past three months. This lack of employment growth – while the labour force has grown by around 170k per month – is behind the unemployment rate’s 0.5ppt rise since April, and the U6 measure of underemployment’s 0.6ppt gain. At 3.9%, the unemployment rate is now above the year-end forecast of FOMC members at the time of their September meeting and just 0.2ppts below the peak rate the Committee expects through 2024 and 2025. Available detail from the business surveys points to a further deterioration in the current pace of employment, making a continuation of the six month uptrend in unemployment and underemployment likely.

The consequences for wage growth of the resetting of demand and supply have already been significant, average hourly earnings growth decelerating from a recent peak of 5.9%yr in mid-2022 to 4.1%yr currently. With the current rate only marginally above core PCE inflation of 3.7%yr at September, the current nominal wage pulse points to a slow healing of real wages from their pandemic lows.

Overall, the US labour is still in robust structural health, yet it is evident that the heat has come out and downside risks for employment and household incomes are forming. To be clear, this is not an assessment based on October’s data alone, but rather the outcomes of the past six months, with the full effect of tight financial and credit conditions still to be felt.

We remain of the view that the FOMC will soon have to shift to a much more balanced view of the outlook and begin making real-time assessments of the appropriate degree of policy restrictiveness. Through 2024, with growth below-trend, this will certainly lead to a lower level of interest rates than today. As has been the case on the way up however, how the term premium and other elements of financial conditions evolve will dictate the precise scale and timing of adjustments to the fed funds rate by the FOMC.